Looking towards plastic alternatives

Have you heard the news? In December of 2021, a draft proposal was released that would ban six single-use plastic items. Following the release of the proposed Single-Use Plastic Prohibition Regulations the federal government has published a report to provide Guidance for Selecting Alternatives to the Single-Use Plastics. The guide gives an overview of how to select plastic alternatives as well as the variety of options available as alternatives to plastic. It’s meant to help businesses, ranging from manufacturers, importers, distributors and retailers of single-use plastic items to foodservice businesses and restaurants, in their transition away from single-use plastics.

As we begin to transition away from single-use plastics, this guide suggests that, when considering alternatives, there needs to be an evaluation process to understand the potential impacts of the selected alternative. All alternatives should be evaluated based on its potential for environmental harm and whether the material is value-recovery problematic. Essentially, a business should know if the alternative is more likely to end up damaging the natural environment at the end of its lifecycle, or if the material is difficult or not likely to be recycled at the end of its lifecycle. Where a plastic product is essential to a specific task, which is often the case for many healthcare scenarios, businesses and organizations are prompted to explore opportunities to choose or redesign products in a way that will reduce the amount of plastic waste. In deciding on the appropriate alternative to plastic, businesses can also determine whether the single-use plastic needs to be replaced, or if that product or service can be removed altogether.

There are often two main types of alternatives for single-use plastics: disposables, made of other recyclable or compostable materials. and reusables. The guide proposes that reducing plastics by replacing them with non-plastic equivalents may be an option for some products. For single-use plastic cutlery, stir sticks and straws, there are many non-plastic materials available, such as wood, paper and moulded pulp fibre. Reusables are another alternative presented in the guide and are identified as a solution that eliminates the need for single-use products.

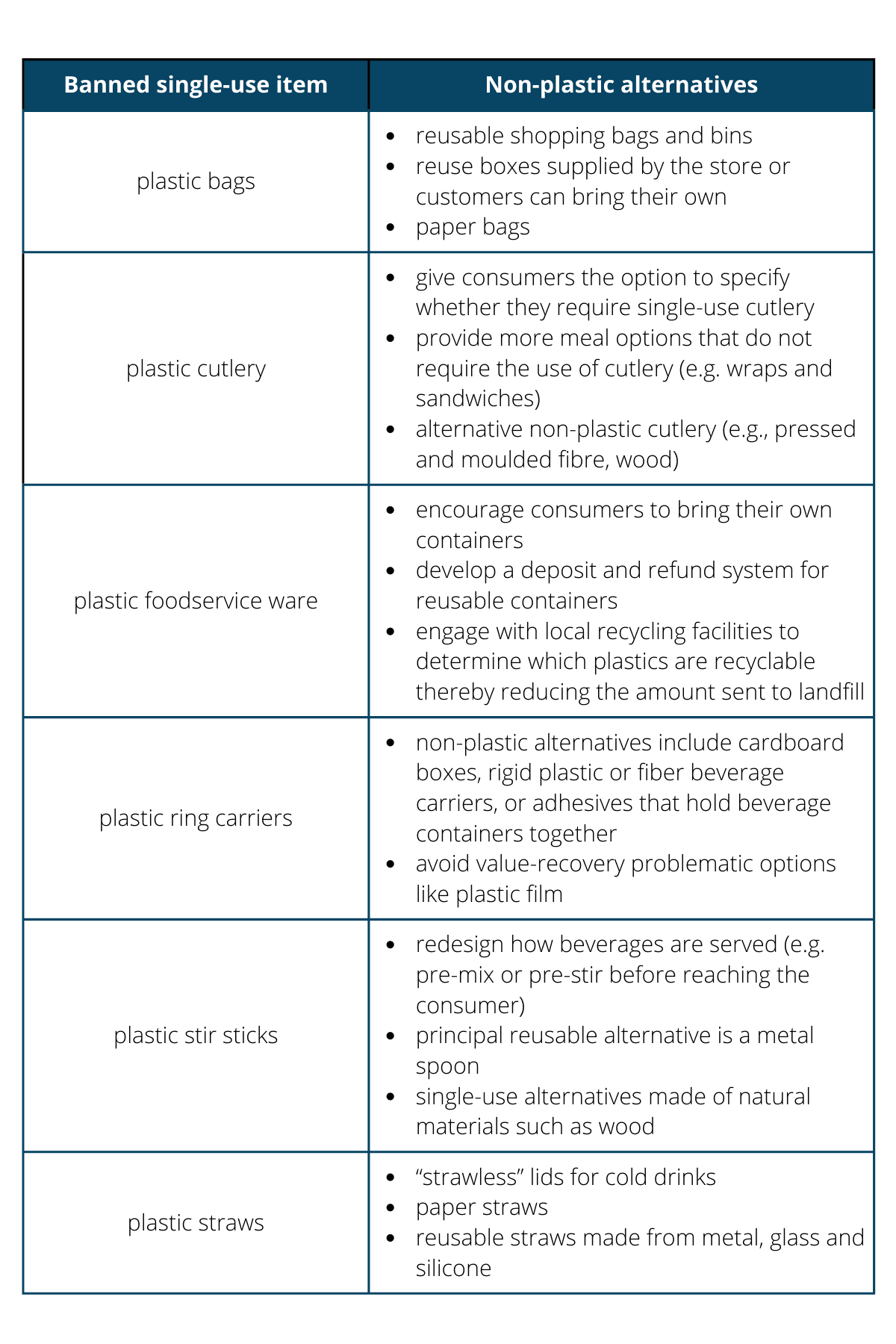

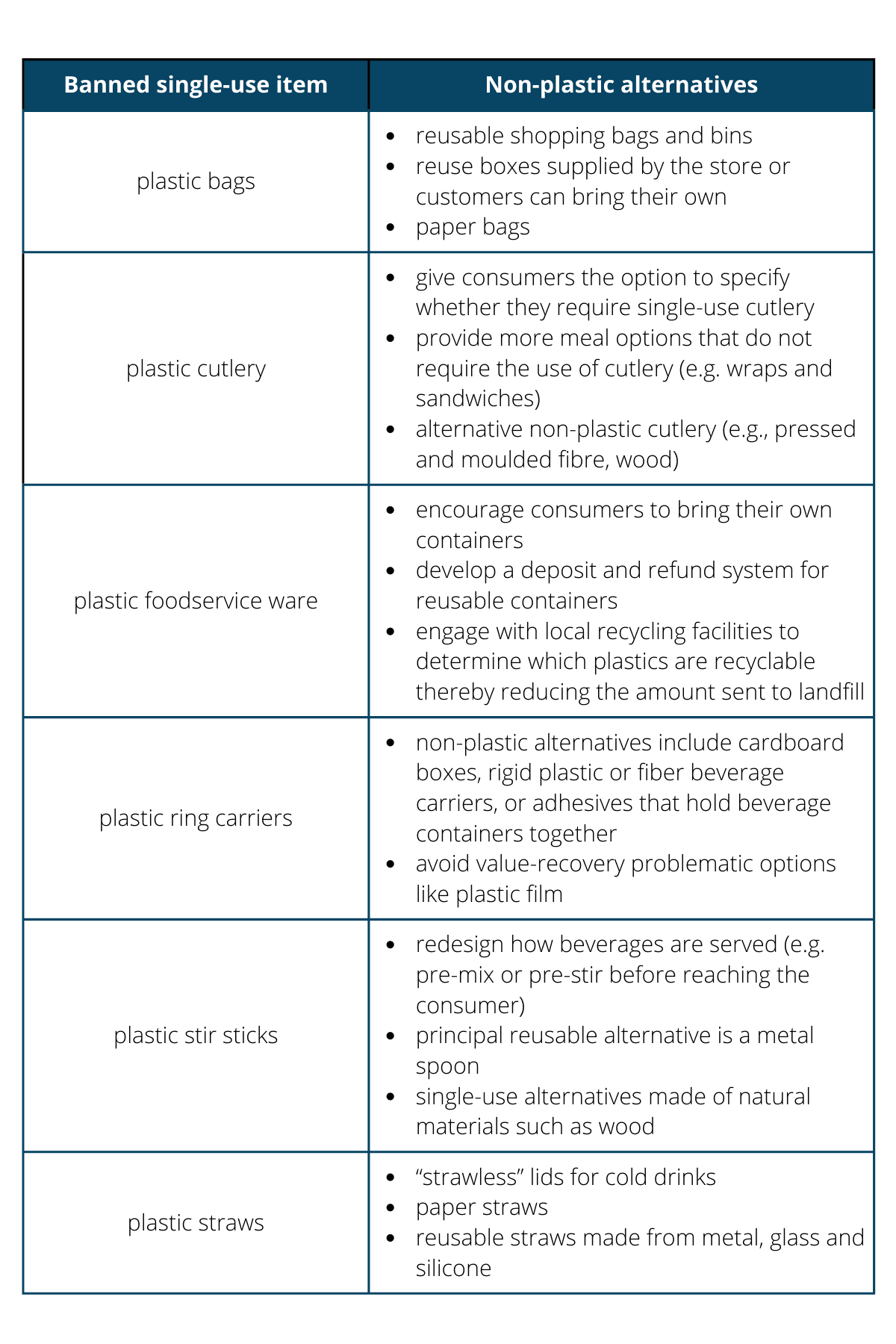

The federal government also presents alternatives specific to the six single-use items covered under the ban: single-use plastic bags, single-use plastic cutlery, single-use plastic food service ware, single-use plastic six-ring carrier, single-use plastic stir sticks, and single-use plastic straws. Check out the table below to see an overview of the guide’s alternatives to single-use plastics.

This list is by no means exhaustive, but it presents a selection of what the federal government acknowledges as viable plastic alternatives. The reusable options in particular are commendable, as they eliminate plastic waste completely. Deposit systems and refill stations are also great strategies to encourage plastic-free behaviours from consumers.

Other options suggested by the guide are not as effective at reducing single-use plastics. The government puts forward that there are also single-use alternatives made from non-banned plastic to which the regulations do not apply. For example, single-use plastic food serviceware containers can still be made from plastics like polyethylene, terephthalate or polypropylene. We know that these plastics can be recycled, but with a 9% plastic recycling rate in Canada, we don’t believe the solution is a different type of single-use plastic. Swapping one problematic material with a similar material that will damage the environment when landfilled isn’t in the spirit of the ban. If 86% of Canadian plastics end up in landfill, single-use alternatives made from non-banned plastics are not the solution.

The guide also advises that reusable or refillable containers often have higher environmental impacts in the manufacturing stage when compared to single-use items. But when used multiple times, these effects are reduced significantly, resulting in a far lower overall impact per reusable item. This is an argument often put forward by large plastic manufacturing coalitions following the ban regulations. It is suggested that plastic alternatives are far worse for the environment, and we need plastic disposables as a low-impact material for manufacturing. The cost of transporting non-plastic materials is frequently referenced, as well as the potential for deforestation caused by the use of paper packaging, and how eliminating single-use plastics will result in far more food waste. The crux of the pro-plastic argument is that it is efficient to manufacture, as only “a small percentage of plastics” impact the environment, and if we improved recycling capacity across Canada, there would be no plastic problem.

Manufacturers offer that only 10% of the materials sent to landfill are considered plastics. Although this may seem like a small percentage, we must think of the vast amount of waste that gets landfilled in Canada every day. Based on a study conducted by the federal government on the amount of waste in Canada, more than 25.7 million tonnes of waste was landfilled in 2018. If we consider 10% of that landfill to be plastic material, we estimate 2.57 million tonnes of plastic entering the landfill. These plastics will take hundreds of years to decompose and release millions of microplastics into our soils and waterways.

While we examine the alternatives to plastic put forward by the federal government, we have to emphasize that a one-for-one replacement of single-use plastic is not the goal. The goal is to change our mindset about the disposability of packaging more generally, and move towards reusing the materials we have already. However, knowing that the transition away from single-use items is essential to achieving that goal, it is important to recognize that not all plastic alternatives are created equal.

There are disadvantages to the production of any single-use material, whether that material is plastic, paper, glass, wood fibre, or aluminum. Transitioning away from a linear economy into a circular economy requires us to look at these materials and find closed loop solutions. We want to be able to reuse our packaging materials endlessly without needing to expend large amounts of energy to manufacture or recycle the product at the end of its useful life. There is no one-size-fits-all approach to plastic waste reduction, but with the flexibility and variety of strategies available to businesses, there should be no hesitation in taking the first step to address the single-use plastic problem. Together, we can demonstrate leadership and find the solutions necessary to prevent further plastic waste and protect our natural environments.